In late 1991, the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) faced a large projected budget shortfall. Ridership was down, unemployment was up, and suburban sprawl was in full effect. Quality of service had deteriorated, and the infrastructure needed repair. The solution was clear: save money by discontinuing service.

In 1992, the CTA announced it was considering shutting down the Lake Street 'L' (now known as the Green Line). The first step in this plan was to close the line’s California Station, which had served some 550 daily riders on Chicago’s West Side. Citing a history of ridership losses and deferred maintenance, the CTA argued that it was no longer economical to operate the line. Service, they said, could be provided by the Congress Line (today’s Blue Line), which was approximately a mile away, and supplemented by bus service.

The threat of a shutdown, and with it the loss of direct access to both the Loop and the suburbs, galvanized residents to form the Lake Street 'L' Coalition.

With assistance from and coordinated by the Neighborhood Capital Budget Group (NCBG), the Coalition initiated a broad-ranging campaign to save the line and keep it open.

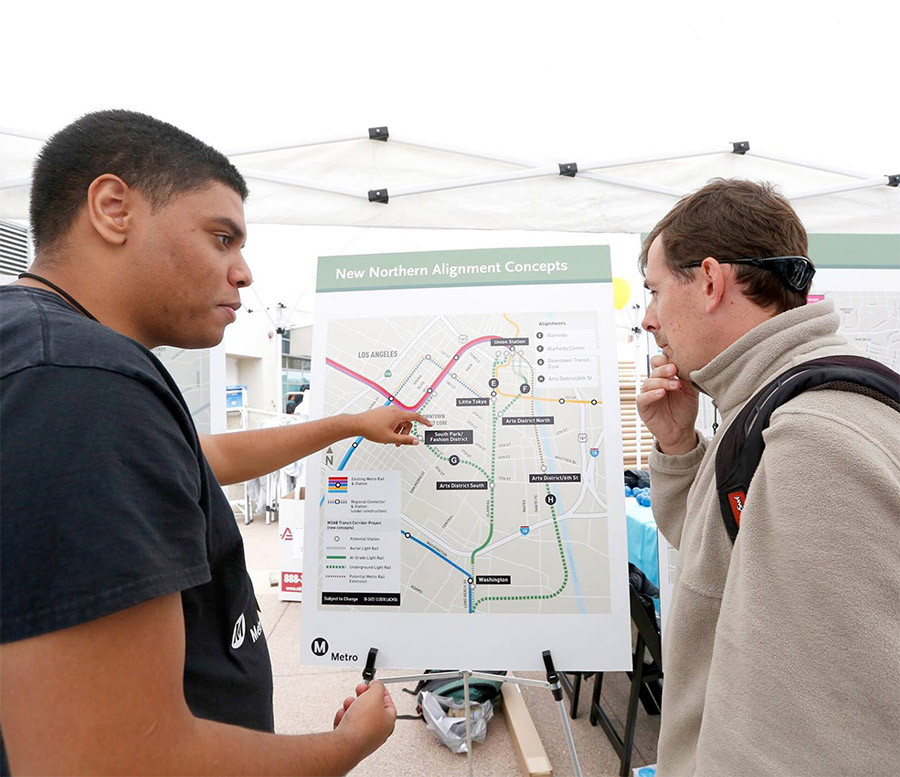

To show the importance of the Lake Street 'L' to the West Side’s economic future, the Coalition launched a pilot transit-oriented development (TOD) planning project for one of the line’s stations at Pulaski. The planning team for this unprecedented project—TOD was a very new concept at the time—included Bethel New Life, Village of Oak Park, Greater Garfield Chamber of Commerce, Transit Riders Authority, Greater North Pulaski Development Corporation, Industrial Council for Northwest Chicago, Garfield Park Advisory Committee, Alderman Ed Smith, and Gammon United Methodist Church (representing the Garfield Austin Interfaith Network, GAIN).

Along with Chicago architect Doug Farr, we provided technical assistance and examined the role that transit reinvestment and TOD could play in reviving inner-city neighborhoods. Because TOD concepts had not been applied to or widely considered in the context of urban neighborhoods, we began educating community residents and groups about the potential for a redevelopment strategy that would target investment around particular station stops in order to spur urban economic development and neighborhood revitalization.

In July 1993, the Coalition unveiled its plan for the Pulaski Station. The plan pointed to a more prosperous future for the line and the communities it served, and positioned the 'L' as the focal point for community reinvestment.

The Pulaski Plan consisted of a self-described “Sustainable ‘Kit of Parts’” with the following key strategies:

- Improve Public Safety—getting to and from the 'L' must be safe, and the station area must be safe.

- Increase Pedestrian Access to Transit and Community Services—it must be easy for community residents to use the 'L.'

- Rebuild Neighborhood Density: Infill and New Housing—a “housing intensification” strategy to take advantage of vacant lots.

- Increase Jobs and Employment for Community Residents—reviving the existing industrial corridor to create jobs and return riders.

- Rebuild the Neighborhood Economy: Retail and Commercial Revitalization—increase transit ridership and reduce automobile use by focusing retail services and amenities near the 'L.'

- Revitalize Open Space—large tracts of vacant land present opportunities for compact development.

- Expand Neighborhood Capacity—new community institutions may need to be created or existing institutions strengthened.

Ten days after the Coalition’s announcement, the CTA announced a new plan for the line—an ambitious, unprecedented, $300 million proposal to rebuild both the Lake Street 'L' on the West Side and the Jackson Park Line (now integrated into the Green Line) on the South Side. The CTA’s plan incorporated some of the key economic and community development ideas proposed by the Coalition, including funding for reconstruction of the elevated structure and the construction of new stations. The concept of mixed-use transit centers was added, mirroring the Pulaski TOD prototype.

After extensive negotiations with community groups, the line was shut down for reconstruction in January 1994 (the largest transit rehabilitation project in the city's history, at that point), and was reopened in May 1996.

We are proud to have served the Coalition and supported its crucial efforts to save the Green Line. Together, our work convinced the CTA that the Green Line was not just a faceless line item in a budget, but connector of communities—an asset to the city that deserved investment and prioritization.

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships