Having always lived in a Black community, I have always had to travel to the next-town-over to buy full groceries. There was one exception. As a child, I often walked to an exceptional grocery store. It was built on the site of an existing forest, anchored economic development, then suddenly closed after seven years. It remains vacant more than twenty years later. I will also note that the grocery store provided video rentals. The lower cost and one-stop-shopping forced the small business video store across the street to shutter. When the grocer closed, my community was left without groceries or videos and had to drive to the next-town-over for both. Living in the city, I have access to corner stores. There is a certain “freedom” in the ability to walk or send children out for food, but the cost savings of walking to the store is deeply counteracted by high prices and unhealthy selection. Many full access chain stores locate themselves just outside of Black communities in nearby white communities. Without delving into the few reasons why, many Black communities regardless of income or class are food deserts. To fully analyze this issue and the associated costs, let’s closely look at the modes of travel in the suburbs and the city.

Modes of Transit

CARS: Even when the store is in an auto-oriented shopping center, Black people must drive a few miles further than White people, enduring the increased cost of car wear and gas mileage. For the carless, using a car hailing service will hike the price of fetching groceries a minimum of $15 during non-peak hours.

BIKES: Bike riding teens from white communities can also explore auto-oriented shopping areas while still being within what most parents would deem “a safe distance from home”. Black bike riding teens going to the same shopping district would be well beyond those “safety” zones. For the wandering bike friendly adult, distance may not be a major issue, but the lack of bike racks is an issue. From my individual observations, I have noticed that grocers in white, urban areas have bike racks in plenty. Grocers in the suburbs or in urban Black areas have none. During my carless years, I hid my bike behind trees, or convinced store employees to stand watch while I returned my Redbox. The suburbs afforded me the ability to pray for my bike’s safety and quickly return. The city is not so kind and significantly short on trees.

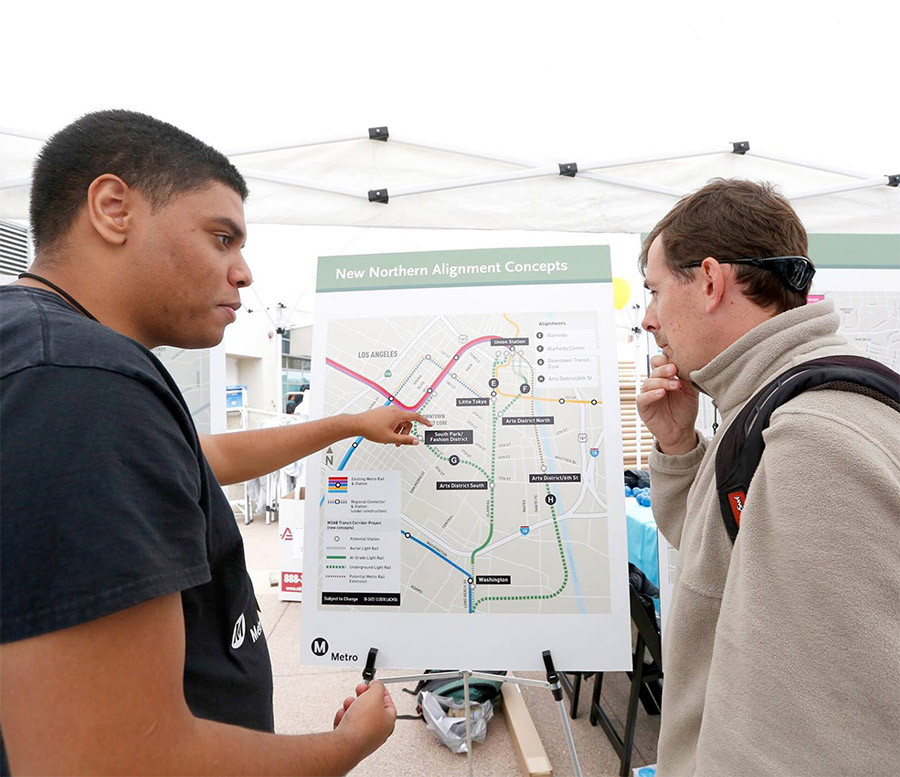

BUSES AND TRAINS: The high frequency trains and rapid bus routes that are the primary mode of transportation for the carless and carbon-footprint-concerned only extend to the city limits. The city limitation for buses only seems to be true in the case of food desert communities. Bus routes that pass through high retail city-suburban areas such as Evergreen Park, Evanston, and Cicero do pass into these suburban places. This makes sense. Bus routes are determined by ridership and shopping centers that have resources like grocery stores create patron density. People privileged enough to live in these areas not only have access to retail resources; They also have complimentary resources like extended bus routes. Therefore, if people have less, than they are determined to need less. Hence, they must expend more of their money and time to obtain what they need. So, the food desert consumer can only access the full line grocer that is three miles away in the next-town-over if she is willing to transfer from a CTA bus to a PACE bus. Thankfully, they are partners and will accept the same fare card, but that doesn’t save consumers any less hassle or time in getting their essential needs. In the days before COVID-19, an old woman could gather her family’s groceries by riding the bus with a personal shopping cart. I have seen men help these unstable ladies lift their carts on and off the high buses. Yet, in these times of social distancing, it’s every old lady for herself. No one will extend a helping hand for fear of contracting a virus. Without that help, how does a person physically incapable of lifting a shopping cart do a mass shopping trip once a week so she can stay in the house the rest of the week? She most likely doesn’t. Unless she can both access and afford food delivery services, she will have to unnecessarily expose herself to keep up with her essential needs. People who rely on public transit for groceries will have to make more frequent bus trips, more frequent transfers, thereby exposing themselves, passengers, and drivers to the COVID-19 virus.

WALKING: No one wants to do any serious grocery shopping on foot, though many do not have any other option. Those who are transit-dependent for groceries will always have one last block to walk. As previously stated, Black people look sideways at those who walk because of necessity. This is truer of those who live in auto-oriented suburbs than the inner city. People may walk for exercise or fresh air but not to conduct errands. As good, bad, or unhealthy as this logic/pride may be, Black people place a stigma on walking. This stigma causes many to constantly look to create methodologies to keep from walking like hailing cars they can’t truly afford or asking favors from friends. During COVID-19, riding in cars with strangers does not promote social distancing and comes with its own risks.

As previously stated, these statements are based on my own observations and experiences with people in various places and not based on data or the research of CNT.

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

RSS Feed

RSS Feed