It will cost about $4.6 trillion to bring U.S. infrastructure to a state of good repair, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers Infrastructure Report Card released last week. If by some miracle our civic leadership raised all that money and hired the engineering and construction firms to do the work, we'd end up with thousands of examples of state-of-the-art 1950s investments.

Let's not do that.

Instead, let's acknowledge the costs of outdated approaches that wasted energy, created sprawl and forced grossly inefficient movement of people and goods. Let's not succumb to the easy path of rebuilding what we've had before when there are so many opportunities to create leaner systems that make our metro areas more competitive, livable and friendly to the environment.

The weakness in conventional strategies is they address only one problem at a time. They rely on hard infrastructure – concrete and steel – instead of tapping into powerful natural systems, like wetlands for drainage or the sun for energy. They rely on large, centralized systems rather than smaller, flexible and resilient networks. And traditional designs put too much emphasis on throughput – moving more cars and trucks, water or sewage, more quickly – rather than local, value-creating economic development.

The presumption that spending trillions of dollars on hardware will create millions of jobs is only half right. It doesn’t take into account that some investment choices are better than others, because they support permanent local employment, or reduce environmental costs, or create a better environment for small businesses.

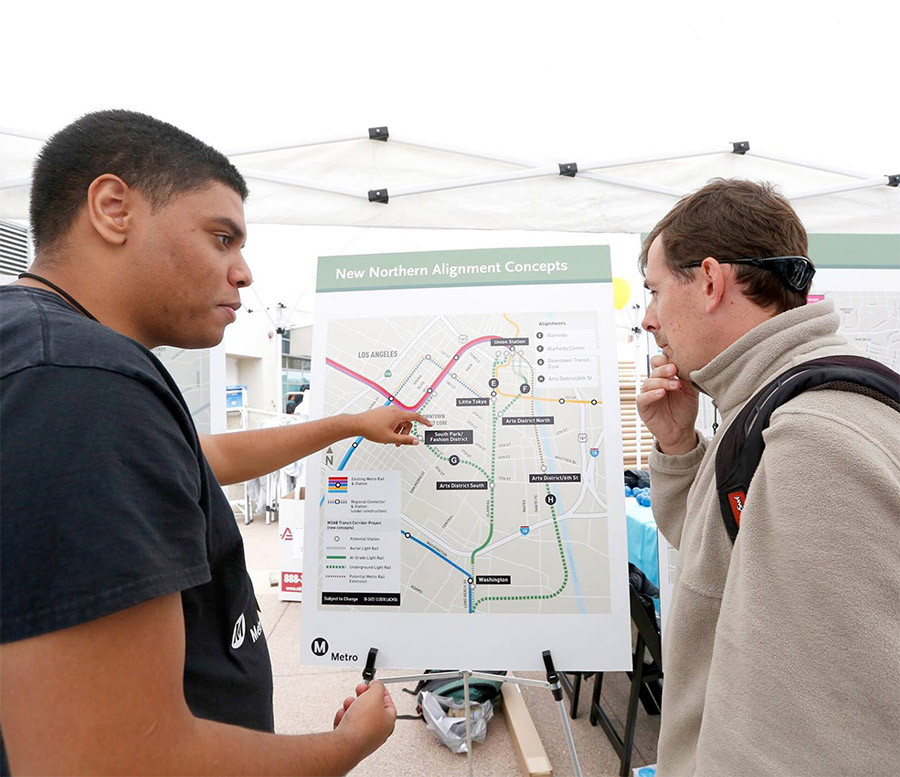

Examples of what not to do are everywhere. Private companies in Texas are pouring money and concrete into a 180-mile toll road encircling Houston, while that same region faces recurring floods because thousands of acres of open space are being paved over for auto-focused development. Eight people died in this year's floods and they won't be the last ones at risk. Suburban leaders southwest of Chicago proudly cut ribbons on massive new warehouses built on greenfield sites, while forklift operators and other workers face harrowing commutes because of inadequate public transportation. U.S. transit systems need $86 billion in improvements, but the biggest opportunities aren't on the tracks and busways. They're on the streets around each station, where progressive land-use and zoning policies could foster mixed-use, mixed-income developments that boost ridership while creating vibrant pedestrian environments and job centers.

For an extreme case of what not to do, look at Flint, MI. With a poverty rate of 41 percent and a strapped budget, the city switched to a lower-cost water supply and skimped on operational controls, causing a lead poisoning epidemic that will plague residents for decades to come. In the face of this crisis, Flint needs to rethink completely its infrastructure spending so that it improves its economy and the well-being of its residents and institutions for the long term.

Rethinking investments

With those kinds of choices in mind, we should begin shifting course.

First and foremost, we should squeeze more efficiency from existing systems – water, sewer, transit, electric – because reducing peak load and spreading out demand allows smaller systems to do the same amount of work. Operated largely by utilities and public agencies, electric systems in some parts of the country have started to invest in their users as partners and sources of efficiency. With marginal costs for this “virtual” energy 50 to 80 percent below the cost of adding traditional power plants, the $10 billion in annual efficiency spending by investor-owned utilities produces a smart ROI.

Second, we can activate vast amounts of underutilized infrastructure and simultaneously reduce transportation demand by filling the gaps in our metro areas instead of extending water pipes, broadband and roadways beyond the suburban fringe.

Third, we should apply a rigorous community-benefits analysis to all major infrastructure investments, looking not just for good systems performance but also lasting, local economic and environmental gains (see Benefits Pyramid below).

The details will differ by metro area, but not the fundamentals of using resources efficiently and supporting job growth. A few starting points:

- Reduce peak loads – Engineers want to size electric and sewer systems to handle maximum loads, but it's far less expensive to "shave" those loads. In Chicago, participants in ComEd's Hourly Pricing program save up to 20 percent by shifting when they use appliances, which helps the utility avoid big investments in peaker power plants and larger distribution systems. Smart grids and other internet-enabled devices can help businesses and residents use less energy and time, benefiting the whole system. Likewise, even the biggest sewers can't handle a 100-year storm as effectively as a well-designed natural drainage system. Repeat flooding happens when stormwater has nowhere to go in Chicago's low- and moderate-income south suburbs – costing $34,000 per home, for example, where some home values are only $100,000 – and in North Shore communities such as Wilmette and Winnetka, too. Converting paved areas to absorbent green landscapes catches raindrops where they fall, and saves up to 80 percent compared to larger sewers that perform the same work.

- Use existing infrastructure – Most older industrial cities have hundreds of acres of underutilized land that's already well served by transportation and utility networks; even sprawling new cities have locations that could be more productive. These sites offer opportunities for housing – affordable, transit-served, close to jobs – as well as job centers such as shared-space developments catering to today's "makers" and creative professionals. They're especially well-suited for the smaller manufacturing operations that are growing in the U.S., because they keep costs down and provide inexpensive space to grow.

- Invest where the people are – Development czars and private companies are often lured by greenfield sites, but they're not thinking clearly about true costs, and how employees will access those sites. Better to build near an urban intermodal rail or trucking facility that is adjacent to residential neighborhoods. Manufacturers benefit not just from rapid, inexpensive transfers of raw materials and finished goods, but from a nearby population looking for good jobs. Too often it is presumed that former industrial sites are best converted to residential developments or big-box stores, instead of taking advantage of their unique infrastructure assets, such as freight rail and high-capacity electric and gas service, plus their proximity to worker-rich communities.

- Develop EcoDistricts – This is the full package, combining multiple efficiencies into a single innovation campus or group of activity centers. Sound futuristic? It was done 100 years ago by Chicago industrialist Frederick Henry Prince, whose Central Manufacturing District used then-state-of-the-art systems to lure 200 companies employing 40,000 people. In today's version, fiber optics, distributed power generation, water reuse, on-site reuse of industrial waste heat and materials, net zero buildings, even indoor vertical farms might be part of the 21st Century model.

Pieces of these strategies are already being tested. One promising approach is creation of "microgrids" that combine clean, on-site generation of electricity with energy storage and intelligent switching to avoid outages. In Chicago's Bronzeville, ComEd is creating a microgrid that will interface with an adjacent microgrid created by the Illinois Institute of Technology. It's a step toward rethinking the utility's 11,000-square-mile territory as a network of efficient neighborhoods, rather than a set of residential, commercial and industrial customer classes.

Vehicles for change

There are plenty of existing platforms on which to build EcoDistricts, from the hundreds of existing campus-level infrastructure networks to the many thousands of neighborhood-scale Business Improvement Districts, Special Service Districts, Tax Increment Financing Districts, Municipal Utility Districts and most recently Innovation Districts. These districts not only offer a needed organizing framework. They also provide innovative, home-grown financing possibilities:

- The Reinvent Phoenix initiative would foster transit-oriented districts along the city's light-rail system by providing financial structures that would attract private capital for predevelopment costs, which could be repaid through a special service district once development is complete.

- Denver needed to finance $12 million in needed improvements to streets, water pipes and sewers, so it agreed to a community proposal to lower the minimum face value for municipal bonds from $5,000 to $500, and to sell them on the internet. The plan was to take bids for five days, but the whole issue sold out in under an hour.

- In Chicago, rather than do battle with legacy rules forbidding the resale of residentially-generated electricity, a “community solar” project aims to allow residents to invest in shared community-scale systems.

Measuring benefits

Getting the most out of infrastructure investments won't be as easy as rebuilding the same old thing. It will require sophisticated analyses and an army of local champions who push decision-makers towards the top of the Benefits Pyramid shown below. Systems are often managed for the bottom half of the pyramid—system condition, performance, and cost. But a huge amount of the value to communities, residents, and business comes from the top half—economic development and livability. By under-designing for and under-investing in those top-level outcomes, we have been shortchanging our communities.

The Benefits Pyramid says three things:

- We need to shift from a world dominated by system benefits to a balanced set of system and community benefits.

- We need to get sharper about the full range of benefits that infrastructure investments can provide, from tangibles like job creation and reductions in cost of living, to others that are no less real, such as health and livability.

- We need to better incorporate long-range costs and benefits, in particular the maintenance burden of larger systems and the number of permanent jobs that create local prosperity.

The bottom tiers of the pyramid will always be important – especially to engineers and elected officials – because they represent system performance, short-term employment benefits and operation costs. But the top tiers bring the deep gains that help a metro area thrive for decades to come. That's the time frame to be thinking about, because infrastructure locks in certain practices and economic impacts, good or bad, for a long time.

The link to poverty

A final factor to consider, as we invest in infrastructure, is how smarter decisions can reduce poverty. The logic here is compelling: by shifting some of a region’s infrastructure investing towards reduced resource demand, there is a tandem reduction in the cost of living. At the request of Memphis Mayor A.C. Wharton, the Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT) created a Blueprint for Prosperity that would reduce poverty by 10 percentage points in 10 years. The benefits would flow from investments in expanded transit service, job access, reduced household cost of living and other cost-reducing investments.

CNT performed similar analyses this year for Akron, Charlotte, Detroit, Gary, Long Beach, Macon-Bibb, Miami-Dade, Philadelphia, San Jose, and St. Paul identifying a set of efficiency strategies that could reduce expenses and expand income to reduce the population living in poverty by 25 percent. Such change is essential, because incomes are not keeping up with rising costs and economic growth is not benefitting all households. This is why places such as Minneapolis and St. Paul can outpace the nation in wage growth and reduced unemployment, yet see a continued increase in poverty.

All of this means that it's time to redirect infrastructure from large-scale, centralized and throughput-oriented systems to more distributed systems that capture benefits for customers and communities. This makes engineering sense, and also boosts the chances for inclusive economic recovery. As climate change increases the risk to communities from abrupt weather events, retrofitting urban places for increased resilience will boost those chances even more.

As our nation faces a multi-trillion-dollar price tag for infrastructure, there's a best way to spend that money. Infrastructure investments must foster transformative land-use and environmental changes that make our metro areas more livable and sustainable. The investments must support jobs and businesses that help our cities become leaner, more productive and more competitive worldwide. And they must bring jobs and economic vitality to all communities, even the poorest. Shared prosperity will result, and that’s not a cost. It’s an investment we can’t afford to miss.

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

RSS Feed

RSS Feed